Turn every challenge into an opportunity with Rapid Assignment Help’s exceptional Assignment Help services.

Canada, which is the second-largest country in the world in terms of land area, is known for its rich cultural diversity and diversified population. Canada's healthcare system is a source of pride for the country due to its dedication to providing universal health care and frequently sets the standard for patient care, medical innovation, and research (Schrewe, 2023). The foundation of Canadian healthcare is the Canada Health Act of 1984, which guarantees access to hospital and physician services without direct costs at the point of care. The system is primarily funded by taxes at the provincial and federal levels. Nevertheless, the system faces difficulties like lengthy wait periods for specific treatments and geographical differences in the quality of care, even with its strong base (Mosadeghrad, 2014). It is crucial to comprehend the nation's current situation, accomplishments, and potential development areas as it continues to refine its healthcare services. The goal of this analysis is to examine Canada's healthcare system, including its financing structures, results, and possible areas for improvement (Keskimaki et al., 2019).

It is anticipated that there will be approximately 38 million people living in Canada in 2022.

With English and French as its two official languages, the population of the nation is diversified and includes a sizable immigrant community (Rumbaut and Massey, 2013). Health outcomes, health service utilization, and health behaviors are all impacted by this diversity. One major worry is the aging population. About 25% of Canadians will be 65 years of age or older by 2030, which will put more pressure on the healthcare system, especially for chronic illnesses (Clavet et al., 2022).

Long-Term Illnesses: Among the main causes of death and disability are respiratory disorders, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes.

Mental Health: There has been an increase in mental health illnesses, especially anxiety and depression, and there is a growing emphasis on mental health service accessibility (Singh, Kumar and Gupta, 2022).

Obesity: As obesity rates rise, there is a greater chance of developing a number of chronic illnesses.

With an average life expectancy of 82 years at birth, Canada boasts one of the longest life expectancies in the world. This demonstrates the nation's dedication to providing healthcare and public health initiatives (Tulchinsky and Varavikova, 2014). The infant mortality rate is about 4.5 per 1,000 live births, which is a low rate. The low rate of maternal mortality further emphasizes the efficacy of programmes related to maternity and child health.

Many Canadians maintain a high standard of living far into old age as a result of successful healthcare interventions. Years of life wasted as a result of early deaths from illnesses including cancer, heart disease, and accidents, however, continue to be causes for concern. Preventive care and health promotion are prioritized, with an emphasis on not just extending life expectancy but also enhancing the quality of those years spent.

Financial Situation and Health Care Spending: Canada is among the top ten economies in the world due to its strong GDP (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies et al., 2020).

About 11% of the nation's GDP is allocated to healthcare. All residents and citizens of Canada will have universal access to hospital and physician services because of this investment (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2022).

Public Health Difficulties:

Wait Times: The length of time patients must wait for specific medical procedures, diagnostic testing, and specialist visits is one of the major problems with the Canadian healthcare system (Rankin, 2021).

Native American Health There are differences in health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities; the former have lower life expectancies, higher incidence of mental health problems, and chronic disease.

Health Indicators:

Fertility Rate: 1.5 live births per woman

Life Expectancy (Female, Male): 85, 81

Infant Mortality Rate: 3.9 deaths per 1,000 live births

Child Mortality Rate: 4.8 per 1,000 live births

Maternal Mortality Rate: 8.3 deaths per 100,000 live births

Prevalence of Obesity: 26.3%

Racial/Ethnic Demographics:

White NH: 75%

Asian: 14%

Native: 5%

Black NH: 3%

Hispanic/Latino: 2%

Other: 1%

Age Structure:

0-14 years: 15.4%

15-24 years: 11.6%

25-54 years: 39.6%

55-64 years: 14.2%

65 years and over: 19.1%

The primary function of the federal government in the healthcare sector is to finance the territories and provinces via the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) (Canada, 2023). This cash, which is allocated based on per capita income, is used to assist the provision of healthcare services. Within their borders, the provinces and territories are primarily in charge of organising and providing healthcare services.

Get assistance from our PROFESSIONAL ASSIGNMENT WRITERS to receive 100% assured AI-free and high-quality documents on time, ensuring an A+ grade in all subjects.

Every province and territory is in charge of overseeing its own healthcare system, and they have the power to decide how much healthcare is funded, what treatments are covered, and how healthcare delivery is structured. Their healthcare insurance programmes, which cover the majority of resident medical services, are their responsibility to run and fund (Tikkanen et al., 2020).

Regardless of their financial situation, all Canadian citizens and permanent residents are entitled to medically necessary healthcare treatments. Publicly accountable authorities must make decisions about healthcare financing and services in order for the healthcare system to be publicly administered.

All hospital and physician services that are deemed medically necessary must be covered by the health insurance policies. When a Canadian moves or travels within the country, their insurance should follow them. They should be able to obtain healthcare services in any province or territory. Preferences for healthcare should be based only on need, with no restrictions on income or other resources (Internationalinsurance, 2023). Hospital stays, doctor visits, and other medically required healthcare services are covered by Medicare.

In Canada, a mix of public and private healthcare providers and organisations offer healthcare services (European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies et al., 2020b). In contrast to many family doctors and specialists who work in private practises and are paid on a fee-for-service basis, the majority of hospitals are funded and run by the government. The healthcare system also depends heavily on other healthcare personnel, including nurses, chemists, and allied health specialists. Many Canadians opt to obtain private supplemental health insurance to cover treatments not covered by the public system, even though Medicare covers essential healthcare services. Prescription medications, dental treatment, vision care, and other services may be among them (Pacific, 2020).

Within their borders, healthcare provider licencing and delivery are governed and monitored by provincial and territorial administrations.

To guarantee that the values of the Canada Health Act are respected, the federal government, through organisations such as Health Canada, offers national supervision, direction, and financial support. The Canadian healthcare system must deal with issues like controlling costs, reducing wait times for certain services, and guaranteeing effectiveness and coordination between healthcare services and providers (Youn, Geismar and Pinedo, 2022).

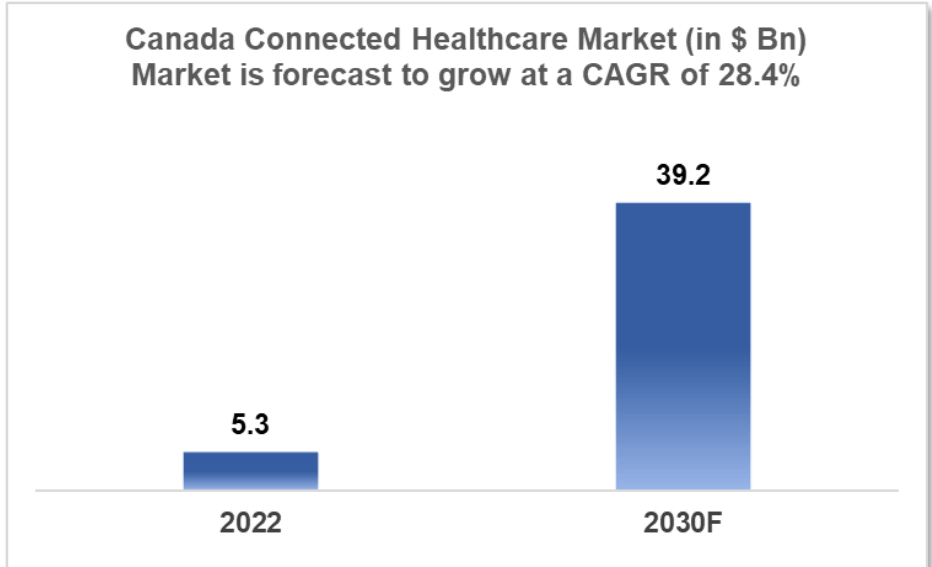

Figure 1: Canadian health market

(Source: Insights, 2022)

The projected value of Canada's connected healthcare market in 2022 was $5.309 billion (Insights, 2022). With a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 28.4%, it is anticipated to develop significantly and reach an estimated market size of $39.221 billion by 2030. The Canadian healthcare industry is predicted to increase at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 10.19%, from $1,638.00 million in 2023 to $2,415.00 million in 2027 (Statista, 2022).

One of the biggest countries in the world, Canada boasts a strong free-market economy that supports a variety of industries, from tiny owner-managed businesses to giant international conglomerates (Thanthong-Knight, 2023). In the past, the export of agricultural staples, particularly grain, as well as the creation and marketing of exports of natural resources, such as minerals, oil, and gas, and forest products, have been vital to Canada's economy.

A mixed public-private paradigm characterises the healthcare system in Canada. Healthcare services are provided by the private sector, with help from the state sector. There are regional variations in Canada's national healthcare service procurement scheme. Regulations are specific to each province and might differ greatly between areas and service providers. Approximately 10.84% of Canada's GDP was allocated to healthcare in 2019, indicating a substantial commitment in this area (WHSF, 2022a). The out-of-pocket cost as a percentage of current healthcare spending is approximately 14.91%, demonstrating that personal contributions pay a portion of healthcare costs (WHSF, 2022b).

Most Canadians have good opinions about how technology is affecting healthcare. They believe that technology will improve their ability to communicate with healthcare professionals and will improve their own experiences receiving care.

But there are worries about access to private healthcare, privacy violation, and the loss of the human element in healthcare. The Canadian healthcare industry is expanding and changing, especially in sectors like digital health and connected healthcare (Li and Carayon, 2021). The nation's healthcare system, which varies by province, incorporates aspects of the public and private sectors. The Canadian healthcare industry plays a vital role in the country's economy and is always changing to meet the demands and expectations of the populace(Marcu, 2021).

The Canadian healthcare system is frequently praised as an example of easily available healthcare for everybody. Also referred to as Medicare, it is a cornerstone of the nation's social structure. This approach is based on a combination of public and private finance. Healthcare in Canada is mostly funded by the commercial sector, despite the majority of money coming from the public sector (Dutescu and Hillier, 2021). With the help of this innovative strategy, Canadians can receive medically necessary care without having to bear crippling out-of-pocket expenses.

Four main sources of funding are used to support the healthcare system: general tax revenue from provinces and territories, federal transfers, the Canada Health Transfer (CHT), and additional fiscal transfers (Naylor, Boozary and Adams, 2020). The equal distribution of resources across the country and their sustainability are guaranteed by this diverse funding method.

Public vs. Private Contribution: The public sector provides around 70% of healthcare funding, highlighting the government's crucial role in delivering necessary care. The private sector contributes the remaining thirty percent, which covers employer-sponsored healthcare coverage, out-of-pocket costs, and additional insurance. The optimisation of healthcare services is made possible by this balance between public and private resources.

Universal Access: The Canadian healthcare system is distinguished by its dedication to universality. Regardless of their financial situation, all Canadian citizens and permanent residents are entitled to obtain medically essential care. This dedication to universality guarantees that everyone has access to necessary treatment, enhancing Canada's standing as a nation that provides fair healthcare.

Comprehensive Coverage: Medicare provides hospital and physician services, which are the foundation of the healthcare system, with guaranteed coverage. Despite the breadth of this universal coverage, some treatments are excluded, including prescription medication, dental care, and vision care. This has caused a large number of Canadians to add private insurance to their healthcare.

Even though they vary, prescription medication costs in Canada are still reasonably low when compared to some other nations. For general health, having access to essential pharmaceuticals is essential, and the Canadian government actively works to strike a balance between drug availability and innovation and price (Lohman et al., 2022).

The advancement of healthcare in the nation is greatly aided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). Working with partners and researchers, CIHR, Canada's government funding agency for health research, supports discoveries and innovations that improve the country's healthcare system. Canada aims to enhance healthcare outcomes and delivery by funding research, taking into account the changing demands of the populace.

The healthcare system in Canada is not without its difficulties, despite its numerous advantages. Notable problems include the need for more medical personnel, the difficulty of guaranteeing prompt access to care, the ageing population's rising burden on the system, and worries about bureaucratic procedures that may compromise accessibility and efficiency. Canada's healthcare system, which is mostly financed by taxes, is a model of universal healthcare that combines contributions from the public and private sectors in a novel way. This strategy ensures that Canadians can access essential medical care without worrying about bankrupting costs. Even though the system is extensive, there are still issues, and ongoing innovation and research often supported by institutions like CIHR are crucial to addressing the changing healthcare requirements of the Canadian public. A vital part of Canada's social fabric, the public-private collaboration in funding ensures the accessibility and sustainability of healthcare services.

Canada's healthcare system, which receives funding from around 11% of GDP, is a vital component of the country's effort to guarantee that everyone has access to high-quality healthcare (Valle, 2021). The country's commitment to provide healthcare to all is reflected in the present funding mechanism, which is mostly based on a worldwide budget system. This paradigm guarantees that healthcare providers receive a fixed amount of funding, regardless of the number of patients treated or the calibre of care provided (CHSPR, 2023). Even if the global budget system upholds the values of accessibility and universality, it is crucial to recognise the difficulties it presents and the continuous attempts to overcome them.

The global budget model is firmly based in the principles of inclusivity and equity. It distributes a fixed sum of money to healthcare providers. It ensures that everyone in Canada, regardless of financial situation, has access to basic healthcare services. It does, however, have some difficulties, just like any other system. The main obstacle is financial limitations. Under the global budget model, fixed financing may result in resource constraints that frequently cause a scarcity of medical personnel, protracted treatment wait times, and strain on the healthcare system (Valle, 2021). These limitations may make it more difficult for the system to adapt to changing patient needs and rising healthcare demands.

The possible absence of incentives for efficiency raises other concerns. Critics contend that in a system where their money is fixed, healthcare professionals could not be sufficiently motivated to innovate or function efficiently. Put another way, there might be less motivation to raise the standard of care, optimise workflow, or enhance patient experiences in the absence of monetary rewards linked to performance. Additionally, the distribution of funding under the global budget model would not always be in line with the particular healthcare requirements of Canada's various populations or regions (Tikkanen et al., 2020). This may lead to differences in the way healthcare is delivered, with certain regions having more difficulty than others in providing quality care because of resource constraints.

Accountability concerns are another issue raised by the global budget approach. Because financing isn't correlated with patient outcomes or performance measures, it gets harder to guarantee high-quality care is provided (Eriksson, Levin and Nedlund, 2022). In certain cases, the lack of clear financial penalties for poor performance can lessen the motivation to reach quality standards.

ABF, bundled payments, and integrated financing models are a few of the alternative funding models that several Canadian governments have investigated in response to these difficulties (Barber, Lorenzoni and Ong, 2019). Funds are distributed by ABF to healthcare providers according to the kinds and amounts of services they offer as well as the complexity of the patient populations they serve. This approach may raise the standard of service and provide financial incentives for effectiveness. A more modern funding model called "bundled payments" uses a single payment to cover all medical care associated with a particular ailment or medical event within a predetermined time frame (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2022). This improves patient continuity of care and fosters more coordination among healthcare providers. In order to provide a more comprehensive approach to patient care, integrated funding models seek to improve coordination and integration across many healthcare sectors, including primary care, acute care, mental health, and pharmaceuticals. Both patients and policymakers place a high value on service quality while seeking high-quality medical care. This includes how well healthcare services support evidence-based treatment and improve intended health outcomes (Laberge et al., 2022). The healthcare landscape is greatly influenced by funding methods, yet in order to maintain the greatest level of treatment, quality assurance procedures, strict standards, and accountability frameworks must be added (CHSPR, 2023).

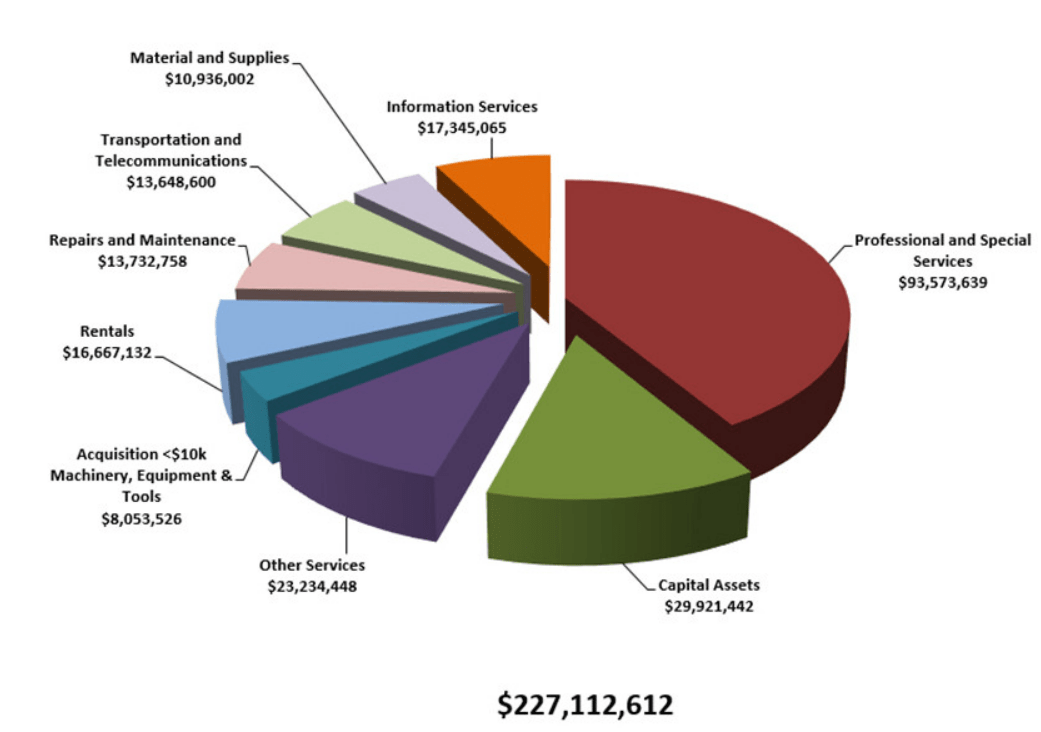

Figure 2: Planned procurement summary: assets and acquired services

(Source: Canada, 2020)

The department's proactive disclosure efforts are greatly aided by Health Canada's Procurement Plan for the 2019–2020 fiscal year. It offers a high-level overview of the department's planned procurement activities for the year and openness about the distribution of public funds for the purchase of goods and services (Canada, 2020). It is imperative to acknowledge that this plan does not constitute an invitation to tender or request for proposals, nor does it imply an official government commitment to buy any particular assets or services (Barber, Lorenzoni and Ong, 2019). Rather, it serves as a strategic overview of Health Canada's procurement goals.

A set of general guidelines must be followed during the purchase process. These guidelines are intended to make sure that government contracting is carried out in a way that is honest and prudent enough to stand up to public scrutiny (OECD, 2021). They represent equity in the use of public monies and facilitate access and competitiveness. Government procurement should also assist long-term industrial and regional development, give priority to operational needs, and be in line with a number of national goals, including the economic development of Aboriginal people. Government procurement must also adhere to international trade accords including the CPTPP, WTO-AGP, CFTA, and NAFTA (Government of Canada, 2022).

In order to guarantee that Canadians have access to adequate and efficient medical treatment, Health Canada assumes a leading role in advocating for sustainable healthcare systems. It works with the governments of the provinces and territories and provides financial agreements to important health partners who are enhancing the health system (Nguyen et al., 2020).

The department evaluates, manages, and disseminates health and safety risks related to a range of factors, including food, chemicals, pesticides, tobacco, environmental factors, consumer goods, and controlled substances. It collaborates closely with both domestic and foreign partners in this endeavour (Laberge et al., 2022). Its goal is to guarantee that Canadians are equipped with the knowledge necessary to make wise choices regarding their health and well-being.

The 2019–2020 Health Canada Departmental Plan outlines Health Canada's priorities, which are in keeping with the organization's procurement operations. In order to comply with laws, policies, and trade agreements of the Government of Canada, the department understands that flexibility and agility are necessary in the planning and implementation of its procurement processes.

Health Canada oversees and manages its procurement operations through a strong governance framework. It uses an electronic standardised business process mapping system and is subject to audits and evaluations of procurement by a number of agencies, such as the Office of the Procurement Ombudsman and the Office of the Auditor General (Canada, 2020). This improves the department's procurement procedures and guarantees adherence to rules and regulations.

Health Canada prioritises competitive procurement whenever feasible when it comes to procurement rules. In order to ensure a fair and competitive process for procurements subject to national and international trade agreements, the department uses Buyandsell.gc.ca to request tender bids from potential vendors (Government of Canada, 2022a). In order to facilitate effective procurement, it also makes use of supply agreements and standing offer agreements for a range of products and services. Health Canada requests tender bids from three or more potential suppliers for requirements that are not covered by trade agreements when the benefits of competition are achievable.

The department uses the internet platform Buyandsell.gc.ca to notify prospective bidders about government contracting opportunities. Through this platform, it notifies vendors of its intention to award a contract directly to a supplier and requests qualifications statements from qualified suppliers. These notices are known as Advanced Contract Award Notices (ACAN) (Government of Canada, 2021). Planned Procurement Volumes: By consolidating buys, Health Canada hopes to find economies of scale through its procurement planning process. As a result, standing offer agreements are used more effectively and with greater flexibility. Additionally, the department finds ways to improve service delivery. Planned expenditures totaling $227.1 million for purchased services and other assets were indicated for the 2019–20 fiscal year (Sec.gov, 2022).

In Canada's healthcare system, the economic assessment of healthcare interventions including mental health interventions is crucial. In order to achieve the greatest potential health outcomes for the population, policymakers and healthcare practitioners may make well-informed decisions about where to direct resources thanks to its crucial role as a tool for healthcare planning and resource allocation (Shah et al., 2023). Due to the limited resources available to Canada's publicly financed healthcare system, it is crucial to give priority to interventions that provide the best return on investment in order to ensure that resources are spent effectively. A key component of accountability is economic evaluation, which provides a framework for determining how well public monies are being spent in the healthcare industry. These assessments help to raise the general standard of healthcare services by pinpointing opportunities for efficiency gains and quality improvement (Li and Carayon, 2021). In order to evaluate the costs and advantages of interventions, this evidence-based method uses empirical data, guaranteeing that healthcare decisions are supported by facts and research.

Economic evaluation in Canada includes a range of analyses, including budget impact analysis (BIA), cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), and cost-benefit analysis (CBA). These studies aid in calculating the financial advantages of an intervention as well as the cost per unit of health gain and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) (Brent, 2023). In the context of mental health interventions, these evaluations frequently entail assessing the financial viability of programmes or therapies in relation to increased quality of life, decreased impairment, and better well-being.

There are particular difficulties when doing economic assessments in the context of mental health interventions, including quantifying health outcomes, taking long-term effects into account, and dealing with stigma and access restrictions. Furthermore, because mental health is complex and requires cooperation between mental health professionals, economists, and healthcare providers, an interdisciplinary approach is required to fully assess the impact of the intervention (Canada, 2023). The availability of data is also essential to guaranteeing the validity of these assessments, especially patient-reported outcomes and long-term follow-up data.

In summary, the economic assessment of healthcare interventions especially those pertaining to mental health is essential to maximising resource allocation in Canada's healthcare system. It guarantees that the population's benefits are optimised through the direction of healthcare spending, all the while maintaining accountability and evidence-based decision-making. Notwithstanding the particular difficulties presented by mental health interventions, continuous attempts to improve data collecting and assessment techniques are necessary to gain a better understanding of and enhance the economic assessment of these crucial services, which will eventually improve Canadians' quality of life (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2022).

The distribution and fairness of healthcare are fundamental tenets of Canada's healthcare system, which strives to guarantee that healthcare services are equitable and available to all residents of the large and diverse country. Geographic allocation plays a role in healthcare distribution, with the goal of reaching both urban and rural areas with medical experts and infrastructure. Overcoming the difficulties of providing primary care and specialised services, such as mental health, in rural places is crucial (Laberge et al., 2022). Technological advancements such as telehealth serve to increase accessibility by bridging geographical divides and providing virtual healthcare services, which are particularly helpful in remote areas.

Beyond geographic differences, healthcare equity addresses inequalities based on age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. In order to ensure that everyone has an equal chance to reach their utmost level of health, Canada is committed to eradicating gaps in health outcomes (OECD, 2021). This entails making certain that socioeconomic background and income do not restrict access to high-quality healthcare, offering varied populations culturally competent treatment, and guaranteeing that healthcare is age- and gender-appropriate. In Canada, encouraging health and prevention, lowering access obstacles, training healthcare professionals in cultural competency, and gathering and analysing data to spot inequities are some of the strategies for attaining healthcare equity (Zghal et al., 2020). The fundamental tenets of healthcare distribution and fairness in Canada are universal access and inclusion, guaranteeing that all citizens, regardless of where they live or come from, have access to high-quality healthcare.

A fundamental tenet of health systems around the globe is equity in the distribution of healthcare resources. It provides the cornerstone for attaining equity in the delivery of healthcare services, guaranteeing that people and communities have equal access to essential care. The proper allocation of medical supplies and equipment highlights the need of allocating these essential resources in accordance with each person's healthcare needs, fostering equity and fair access among demographic groups that are determined by geography (WHSF, 2022a).

The problem of unequal distribution of health resources is widespread and not limited to any one area. A multitude of nations, including those in Europe and emerging countries such as Thailand, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and India, have observed differences in the distribution of health resources according to factors such as income, location, and ethnicity. These disparities add to the more general notion of health inequality, which also includes differences in access to medical care (WHSF, 2022b). These unjust allocations, which are the outcome of institutional defects, lead to injustice in the healthcare system.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) emphasises how crucial the fairness concept is for dividing up and allocating resources for health care. The importance of resolving these inequities is underscored by the fact that equitable distribution is a crucial metric for assessing the effectiveness of health systems.

Many countries' constitutions and institutional frameworks recognise the right to healthcare and medical treatment as a basic human right. Although this right is acknowledged everywhere, obtaining equitable access is significantly hampered by the uneven regional distribution of health resources. The lack of planning, data, and healthcare professionals in developing nations frequently results in the unequal distribution of resources. Disparities in health outcomes may result from people's limited access to necessary healthcare services due to this inequality (Thanthong-Knight, 2023).

In summary, a key component of healthcare systems and a means of advancing justice and fairness in the delivery of healthcare services is the equitable allocation of healthcare resources (Shah et al., 2023). To guarantee that all people and communities, regardless of their location, ethnicity, or financial level, have equal access to the healthcare they require, it is imperative that the worldwide challenge of unequal resource allocation be addressed.

Recommendations

Needs-Based Resource Allocation: Changing to a needs-based approach is one of the most important stages towards attaining equitable resource allocation in healthcare. This method requires a data-driven evaluation of the healthcare requirements of various populations or regions, accounting for variables including disease prevalence, demography, and social determinants of health. Establishing clear criteria and rules for resource distribution is crucial to the efficient implementation of this advice. It also ensures that the process is open to the public and grounded in actual evidence. In addition, it is crucial to conduct frequent assessments and modify resource allocations in order to adapt to evolving healthcare requirements (OECD, 2021). In order to guarantee that underprivileged populations receive the healthcare services they require, needs-based resource allocation is a crucial first step in allocating resources where they are most urgently needed.

Equity-Oriented Policies: It is imperative that governments and healthcare institutions proactively implement strategies and policies that give equity first priority when allocating resources for healthcare (Government of Canada, 2022a). This can be accomplished by creating moral frameworks that specifically highlight fair resource distribution as a fundamental idea that directs decision-making at all healthcare management levels. Identifying possible inequities and creating mitigation strategies are made easier with the implementation of equity impact assessments for healthcare policies and treatments. Incorporating communities and stakeholders into the decision-making process additionally guarantees that the distinct requirements and inclinations of impacted groups are taken into account (Nguyen et al., 2020). Policies that prioritise equity play a crucial role in mitigating healthcare inequalities and cultivating a perception of impartiality and social justice in the distribution of resources.

Capacity Building and Investment: The healthcare system needs to be heavily invested in in order to address the issue of unequal resource allocation in healthcare. This includes providing incentives to healthcare professionals to work in places where there is a shortage in order to assist in the development of the healthcare workforce, especially in neglected areas. Infrastructure investment is also essential; it includes building and maintaining medical facilities in underprivileged areas and using telemedicine and mobile clinics to fill up gaps in coverage. Furthermore, evidence-based resource allocation is made possible by investments in technology and data collection, which are necessary for accurate and accessible data (Mosadeghrad, 2021). Building a robust and responsive healthcare system that can adjust to changing healthcare requirements and successfully address inequities depends heavily on capacity building and investment.

Conclusion

The public sector provides around 70% of healthcare spending, primarily through taxes. The private sector contributes the remaining 30%, which can be used for out-of-pocket costs, private insurance, and employer-sponsored healthcare. The backbone of the healthcare system, Medicare, pays for doctor and hospital treatments at no cost to the patient at the time of service.

Healthcare Funding Models: The global budget system, which gives healthcare providers a set amount of money regardless of the number of people they treat or the calibre of treatment they deliver, is the most common funding model in Canada. The global budget system confronts difficulties because of limited resources, insufficient incentives for efficiency, and possible disparities in resource allocation, even while it supports the principles of accessibility and universality.

The governments of Canada have looked into alternative funding models such bundled payments, integrated finance models, and activity-based funding (ABF) to solve these issues. Funds are distributed by ABF in accordance with the kinds and quantities of services rendered as well as the complexity of patient populations. Bundled payments combine financing for all medical services associated with a certain ailment over a predetermined period of time. The goal of integrated finance models is to improve collaboration between different healthcare sectors.

Systems for Purchasing Healthcare Services: The department's planned procurement operations are outlined in Health Canada's procurement strategy for the 2019–2020 budget year. The strategy places a strong emphasis on accountability and openness when allocating public monies to pay for the acquisition of products and services. To guarantee that government contracting is carried out in a way that is responsible, truthful, and compliant with trade agreements, national objectives, and economic development goals, Health Canada adheres to a set of broad criteria. Canada's healthcare system, which is mostly funded by taxes, is an excellent example of the country's dedication to universal healthcare because it combines funding from the public and private sectors. Canada is not one to let obstacles like long wait times and unequal resource distribution stop it from innovating and exploring new finance models to enhance healthcare delivery.

References

Introduction Get free samples written by our Top-Notch subject experts for taking online Assignment...View and Download

Task 1 Get free samples written by our Top-Notch subject experts for taking online Assignment Help services. 1.1...View and Download

Introduction Get free samples written by our Top-Notch subject experts for taking online Assignment...View and Download

Introduction Get free samples written by our Top-Notch subject experts for taking online Assignment...View and Download

Introduction Get free samples written by our Top-Notch subject experts for taking online Assignment...View and Download

1. Introduction With Rapid Assignment Help, you receive unmatched quality in every project through our exceptional Assignment...View and Download

Copyright 2025 @ Rapid Assignment Help Services

offer valid for limited time only*